Case Series/Study

(CS-092) Novel Application of Umbilical Cord Flowable Tissue Allografts in Sacral Decubitus Ulcers: A Case Study

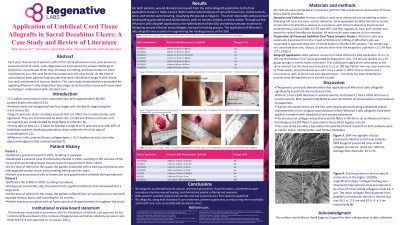

Each year, thousands of patients suffer from sacral decubitus ulcers, also known as pressure ulcers or sores. The current standard of care for sacral decubitus ulcer treatment is expensive and suboptimal, ranging in cost from a 15-dollar tube of Neosporin Ointment to 240,000 dollars for a skin flap surgery. Grade II pressure sores inevitably progress to stage III and IV if not addressed aggressively and early. Late-stage pressure sores present a unique challenge to physicians, particularly when they are deep, tunneling, and have tendon or bone involvement, as is the case for the two patients in this case study. The first patient in this study (referred to as patient 1) was afflicted with a mid-sacral pressure sore with exposed tendon, bone, and tunneling of ten years duration. The second patient in this study (referred to as patient 2) suffered from an ischial pressure sore with exposed tendon, bone, and tunneling for 30 months duration. Both patients exhausted conservative measures, including wound vac placement, oral and IV antibiotic treatment, multiple episodes of sharp debridement, wet-to-dry dressings, silver sulfadiazine dressings, and dehydrated amniotic membrane allograft placements. After failing conservative management, both patients received several applications of Wharton’s Jelly, a mesenchymal connective tissue allograft (MCT), to accelerate wound closure. Conservative management, including sharp debridement, oral antibiotics, and electrical stimulation, was used in conjunction with the WJ allograft applications. At the time of consultation with Dr. Michael Lavor, both patients had sacral decubitus ulcers (SDU) classified as Stage IV with tissue loss and involvement of bone or tendon, according to the National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP). After eight months of standardized wound care treatment combined with six Wharton’s Jelly allograft applications, both patients had wounds showing over 90% contraction in depth, tunneling, and diameter. This case study demonstrates a precedent for applying Wharton’s Jelly allografts in late-stage sacral decubitus ulcers with associated tunneling in combination with standard of care. Future research efforts with Wharton’s Jelly allografts applied to recalcitrant wounds may be directed at the frequency and combination of procedural techniques that best promote granulation tissue formation and volumetric contracture of deep wounds by secondary intention.

Methods:

Results:

Discussion:

.jpeg)